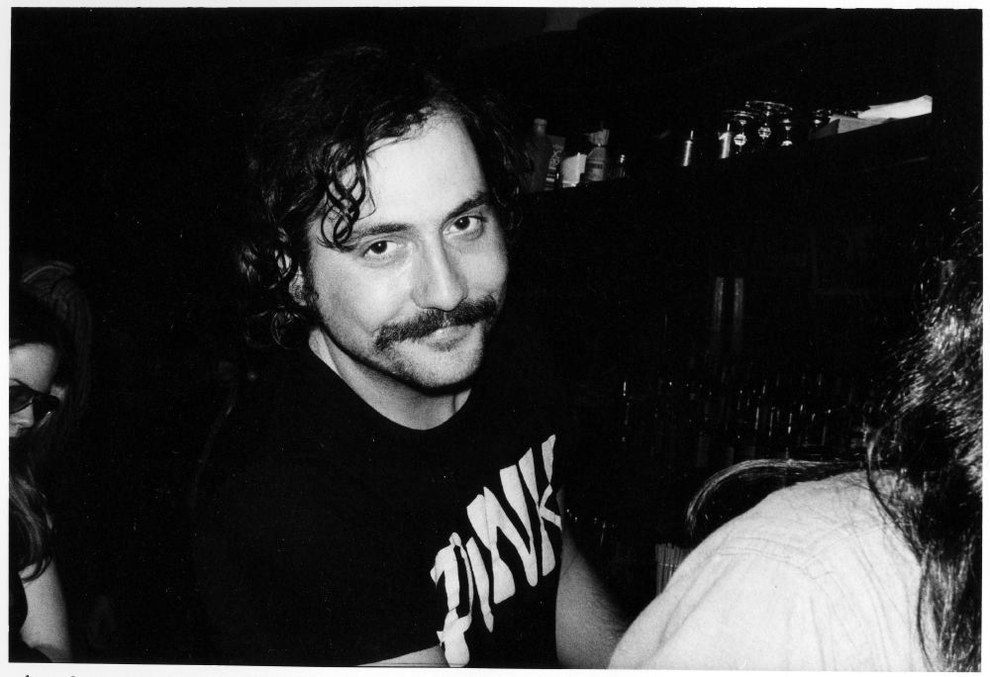

| French literary and cultural critic Roland Barthes, whose Mythologies (1957) sets the stage for modern critiques of material culture |

As we think about the field of English studies in the late 20th and early 21st century we're at home with the idea that our work might focus on subjects other than traditional written texts — audio recordings, videos, photographs, and other art objects, for example, as our work over the last several classes have revealed — but on the esoteric and interdisciplinary fringes, where innovative creative work is being done, there's something even more abstract (and, simultaneously, concrete): the object. Interdisciplinary is the key word here, since the way in which one addresses a given object might touch upon any number of other subject areas, from history to philosophy, economics to sociology, psychology to religion.

We'll start with a few selections from Roland Barthes' Mythologies, a book of brief essays that originally ran as a column in Les Lettres Nouvelles and explore the greater resonances of everyday things. In the second part of the book, Barthes explains the motivation behind his observations, offering the notion of "second-level signification," which builds upon the basic linguistic transaction (i.e. a signifier and a signified combining to form a symbol), moving from denotation to connotation. Still, even if that sentence doesn't make any sense to you at all, the ideas behind Barthes' seductive prose will.

We'll start with a few selections from Roland Barthes' Mythologies, a book of brief essays that originally ran as a column in Les Lettres Nouvelles and explore the greater resonances of everyday things. In the second part of the book, Barthes explains the motivation behind his observations, offering the notion of "second-level signification," which builds upon the basic linguistic transaction (i.e. a signifier and a signified combining to form a symbol), moving from denotation to connotation. Still, even if that sentence doesn't make any sense to you at all, the ideas behind Barthes' seductive prose will.

Roland Barthes, from Mythologies [PDF]

- Soap-powders and Detergents

- Toys

- Wine and Milk

- Steak and Chips

- Plastic

We'll stay in France for our next brief reading, Georges Perec's, "Notes Concerning the Objects That Are on My Work Table" [PDF] — a short portion of the larger series published as Species of Spaces, which is concerned with everyday materiality.

Next, we'll shift gears from the literary mode to something more journalistic, with two examples of contemporary historical writing about objects. I've already talked in class about the Cooper Hewitt Museum's excellent "Object of the Day" column, which takes a brief look at interesting objects from the museum's vast archives, and we'll start by looking at a few selections from there:

- Think Different

- Pluck 'Em!

- Come, All Ye Weary

- Mini-Maglite

- Tea, Anyone?

- Juwel for a Tool

- A Dandy of a Camera

- Sweetheart Toaster

Then, just as records have the 33 1/3 series, and there are numerous similar series dedicated to individual films, objects have now gotten into the act with the "Object Lessons" series of books and essays. So far, full-length books have been released on objects as diverse as the remote control, the golf ball, bread, glass, the phone booth, hair, dust, and doorknobs (among other titles), and The Atlantic has partnered with the series to publish essays in a similar vein. We'll take a look at three such essays for Friday:

| Lydia Burkhalter's collection of gray sweatshirts (from WiC) |

We'll close with two selections from the ambitious collection Women in Clothes. Edited by Sheila Heti, Heidi Julavits, and Leanne Shapton, with contributions from more than 600 other women, this wide ranging book "explores the wide range of motives that inform how women present themselves through clothes, and what style really means" via questionnaires, interviews, short essays, photo galleries and many other hybridized forms.

Were this book not so big and not so expensive, I'd have used it in this class, but hopefully this little taste will spur your interest to explore further: